I’ve never been an entertaining social drinker. The disinhibiting qualities of alcohol that cause others to dance on tabletops and engage in weepy, shirt-rending confessionals merely accelerate my desire to sleep - a curse that has hounded me on multiple continents (and particularly within the beer-saturated borders of the Czech Republic). Coffee, however, has rarely failed to ignite my conversational faculties, for better or worse. Like countless other Gen-X American high schoolers with “weird” interests that denied them a clique affiliation, much of my formative social life was spent huddled over a bottomless mug of cheap, burnt grounds at the lone greasy spoon diner that would tolerate us. Here we’d be routinely scolded by a long-suffering waitress who wondered if we didn’t have “anything better to do” (we didn’t).

The resurgence of coffeehouse culture in the 1990s meant a much more robust quality of drink than the watered-down brew that got me through high school, and with that came an expectedly higher price tag. However, in that glorious, brief window of opportunity after coffee became appreciated as something other than a stimulant for long-haul truckers and disaffected teenagers, and before the Starbucks standardization of the landscape, select coffeehouse proprietors thankfully intuited that their clientele had a peculiar combination of discerning taste and minimal disposable income. So the coffeehouse could, as it had been for previous generations of cultural “marginals”, be sold as a participatory experience or an impromptu laboratory for ideas rather than just a passive site of consumption. That was to be achieved by an implicit commitment to non-trivial, earnestly reflective, honest discourse. I’ve recently wondered how much this personal assessment fit into a larger historical narrative, and if such a vision has a future: as such I recently ended up devouring Brian Cowan’s study The Social Life of Coffee.

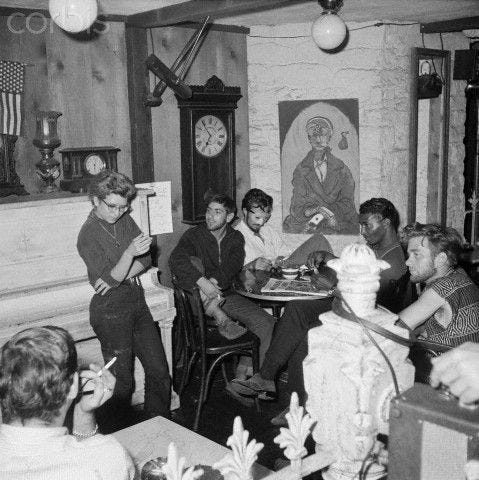

We’re all likely familiar with the more stereotypical images of the coffeehouse from the Beatnik and “hipster” heydays. While the bongo drums, goatees and recitation of free verse over Charlie Parker records are too associated with their time to be deployed unironically today, something of that general attitude of performativity has persisted, and along with it a sense of these places as a “multi-use” site of expressiveness where free-form conversation could exist on an equal footing with similarly inclined music, visual art, cuisine, etc. I remember, for example, the almost confrontationally hip Earwax coffee shop in Chicago’s Wicker Park, which doubled as a ‘zine seller and record store (for some reason they were among the city’s first backers of “digital hardcore” and breakcore records, which make a lot more sense when hyper-caffeinated). Much more recently, I personally attempted to strengthen such associations by booking a series of electronic music concerts at Austin’s Cherrywood Coffee venue, where I was graciously allowed to get away with murder sonically (sadly not the case at an Illusion of Safety performance I witnessed at another now-defunct in Chicago, where the audience began throwing their silverware around in a hostile, sarcastic “emulation” of the shake-rattle-and-roll soundscape unfolding on stage).

The first coffeehouse on record was the Angel, which first opened for business in Oxford in 1650. Markman Ellis notes how “the practice of coffee drinking […] goes back only 350 years in Northern Europe, and only another century or so in Ottoman Istanbul”, and therefore “the associations that we have of coffee and conversation are then distinctly modern.”1 More so, in fact, than the pub or tavern, and this was a point of distinction almost immediately seized upon and embraced by the “virtuosi” or intellegentsia of the 17th and 18th centuries. Its sheer novelty led the early coffeehouse to make some frankly ridiculous attempts at being a “cabinet of curiosities” or exhibition space for kitschy exotica, but they somehow survived this initial phase of silliness to become known as much for their enablement of virtuoso conversation as for their primary item of sale.

Many contemporaneous writers, wits and pamphleteers were also quick to contrast the coffeehouse patrons’ advanced sense of civic engagement (i.e. their propensity for speaking freely on controversial topics) with the endemic submissiveness of tavern regulars. Here is a particularly incendiary example:

“The honest drunken curr,” another pamphlet suggested, “is one of the quietest subjects his majesty has, and most submissive to a monarchyal government. He would not be without a king, if it were no other reason than meerly drinking his health.” Of course, the loyal sot “hates coffee as Ma-homatizm”.2

This is, of course, an idealistic and oversimplified reading, and Cowan’s study reveals that the coffeehouse wasn’t always seen as the pinnacle of civilized life. There was a not insignificant amount of worry over “coffeehouse violence” erupting from impassioned debates, with the understanding that coffee-fueled fisticuffs could be every bit as sincere and intense as what you might now experience at any given sports bar on a Friday night. Cowan notes that things got particularly lively during times of political upheaval (i.e. “the late 1670s and early 1680s, during the post-revolutionary 1690s, and again in the 1710s”). By way of illustration, Cowan mentions a 1683 incident in which

…whig provocateur Titus Oates was struck several times over the head with a cane by one of his opponents. Being wedged in too close to the table, Oates could not retaliate in kind, and so he responded by throwing his dish of hot coffee in the eyes of his assailant.3

Another challenge to the coffeehouse’s civilizing potential came from the kinds of people who, in a striking bit of linkage to more modern times, showed up merely to be seen: banking on the hopes that they might be seen as “wits” or “virtuosi” just by sharing a venue with the genuine article. (This was more of a challenge than it sounds, as even a literary titan like Jonathan Swift was intimidated enough to visit the same coffee house multiple times before daring to say a word.) The most insufferable of the hipster poseurs, never totally absent from coffee culture, have a common ancestor in the London “fop” or “beau,” who put in regular appearances at famous like St. James Coffee House and consumed the news and conversation at these places merely to “collect more material for [their] idle banter, ” i.e. in order to improve their social standing rather than be personally enlightened. A close cousin to the fop - the “newsmonger” - delighted in visiting coffeehouse to experience new information just for the sake of its newness, with no attendant reflection upon its content.

As we now know, the idea of the coffee house would survive the infiltration of these more obnoxious elements, so that they would come to be seen as exceptions to the general rule of mannered, intellectually challenging discourse. The Social Life of Coffee reveals that, among many other things, the coffeehouse did make good on the above boast that it was a forum for “alternative” opinions, centuries before they became the sites of folk singer performances and Beatnik poetry readings. In fact, the coffeehouses of post-Restoration England featured innovations that even today would be considered radical, or would simply never be given an official stamp of approval: many of these establishments acted as makeshift post offices for sending and receiving personal mail, and many others minted and issued their own “coffeehouse tokens” accepted as payment by a limited number of other sympathetic establishments (it should go without saying that this was highly illegal).

However, the coffeehouses’ status as clearing houses for public information would be more important and consequential than any of these activities. Whatever else they might have been, they were not, in the aggregate, the places to find “the quietest subjects his majesty has”. Much in the same way that the government of Charles II frowned upon the coffeehouses’ attempts at breaking the monopoly on legal tender, it had little patience for their dissemination of what was termed “false news” (yet another one for the “how little things have changed” file). Anxieties over the “openness to all comers” that Cowan describes were not at all dissimilar from present-day hand wringing over networked social media’s dissemination of disinformation information inconvenient to the authorities’ legitimacy: particular period concerns included the fear that the coffeehouse would become a “breeding ground for atheism.”

The first major coffeehouse crackdown of note came in 1675, after the appearance of an incendiary tract titled A Letter from a Person of Quality to His Friend in the Country. Essentially outlining a conspiracy to make the crown subservient to the papacy, it incensed the king enough to result in a decree revoking the licenses of coffeehouses and refusing to grant any new licenses. Royal back-pedaling on the issue, and issuing of subsequent decrees, would continue in a byzantine fashion throughout the reign of James II and that of William & Mary, before coffeehouses could earn some sort of re-branding as centers for controlled, “respectable” bourgeois conduct rather than as free exchange of ideas. This was not before numerous other controversies, including one implicating the coffeehouses as spy dens for foreign adversaries. With such accusations in the air, coffeehouse proprietors were actively encouraged to “snitch” on their clientele in exchange for their being allowed to continue doing business.

That enforcement of such kinds was even necessary to begin with may, again, be a testament to the breadth and quality of discourse that took place in the early coffeehouse. Ellis insists upon a twelve-point program of unwritten, but implicit, rules governing the coffeehouse conversation, of which a couple are well worth mentioning. His 3rd and 6th rules, in particular, read as follows:

The discursive economy of the coffee-house is inclusive: so that all opinions might be heard, even those which are diametrically opposed, unfashionable, unlikely to be persuasive.

That the discussion is rational, reasoned skeptical and critical implies that the principles of empirical observation of the eyewitness, of presentation of evidence, and of forensic argument will be adopted—rather than dogmatism, arguments from faith, or attacks on the character of other speakers.

Also of significance, though, are the 9th and 10th rules on this list, merged here into one:

That the coffee-drinkers have opinions about topics that matter is important in forming public opinion or debate: that is, the opinion of an individual matters in the creation of public opinion. Nonetheless, individuals should give way in the face of superior argument or better information (adopting a principle of anti-dogmatism and anti-relativism).4

It’s more or less a commonplace now to insist that such conversational skills can be helped along by certain caffeinated beverages’ promise of alertness, and the (ideally) enhanced critical thinking that follows. However, in all of the writings cited so far, there is a great deal of information on socializing under the influence of java, but a peculiar lack of emphasis on the sensory experience that still distinguishes them, and that enhances that very socialization. Just the smell of these venues is so easily identifiable that anyone familiar with a coffeehouse would be able to easily “fill in the blanks” with regard to the other sensory phenomena available there. I’ve written elsewhere that overwhelming olfactory sensations de-center us by bringing us closer to the earth-bound “animal” world: one which, in plenty of cases, boasts dramatically more powerful olfactory ability than what we possess. In doing so, we strengthen a sense of continuity to something more profound than our strictly human history, which I feel is an essential prerequisite to visualizing a future that offers only “more of the same”.

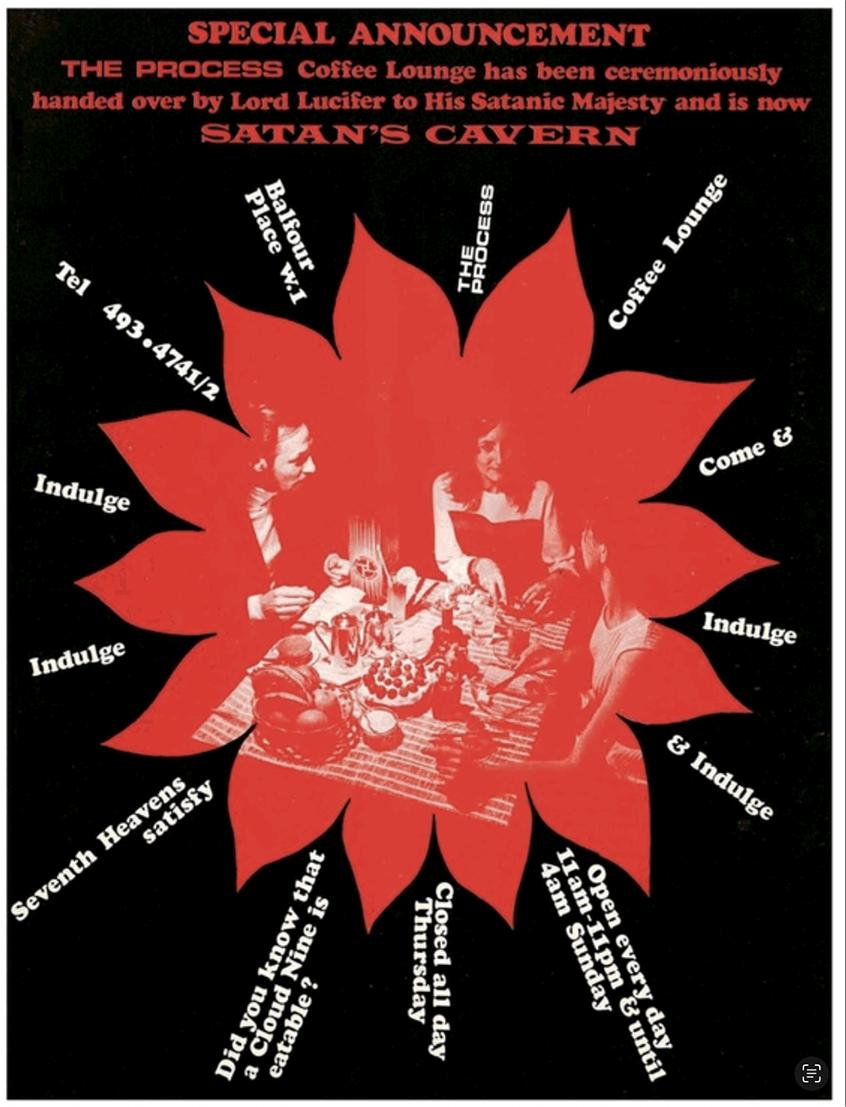

It’s amusing, in light of all that has gone before, to consider that the death of coffeehouse culture has been announced on several occasions. As far back as 1960, a Business Week editorial claimed that the coffee house “turned out to be only a fad…the coffee shop is going the way of the hula hoop”. It’s clear that establishment media editorials like these were hoping to hasten the end of “beatnik” culture by fiat decree (a tradition gleefully carried on by our contemporary propaganda organs), but such premature obituaries can now be filed away with the infamous “guitar groups are on their way out” dismissal of the soon-to-be iconic Beatles. As we now know, the countercultural posture of the Beats would just morph into other 1960s radical movements, and more than just a token number of coffeehouses continued to do a brisk trade. In the mid-1960s, a group as fringe and controversial as the Process Church of the Final Judgement could install a public coffee house in its Mayfair headquarters in London, clearly perceiving that potential recruits of the intellectual caliber desired by the Church were more likely to gravitate towards a coffeehouse than a pub.

Laurel and Robert Vartabedian note that the Beats’ embrace of the coffeehouse was a defiant rejection of the loss of the commons to television; an act that they fit into a larger misguided program of “doing your own thing” which just ensured a future in which “individualistic rather than civic impulses” would be “attended to”.5 Even if we take their failures as a given, there is still a possibility that these spaces can be used to revitalize the currently moribund state of our “civic impulses”. For those of us lucky to have full use of all our sense modalities, the idea of the coffeehouse can still be a genuine alternative to an empire of passive, screen-based visuocentrism, and a place where honest dialogue and full use of our sensory modalities combine to challenge regimes who benefit from their enforced limitation.

Ellis, M. (2008). “An Introduction to the Coffee-House: A Discursive Model”. Language and Communication, (28), pp. 156-164.

Cowan, B. (2005). The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffee-House. New Haven / London: Yale University Press

Ibid.

Ellis (2008).

Klinger-Vartabedian, L., & Vartabedian, R. A. (1992). “Media and Discourse in the Twentieth-Century Coffeehouse Movement.” The Journal of Popular Culture, 26(3), pp. 211–218.