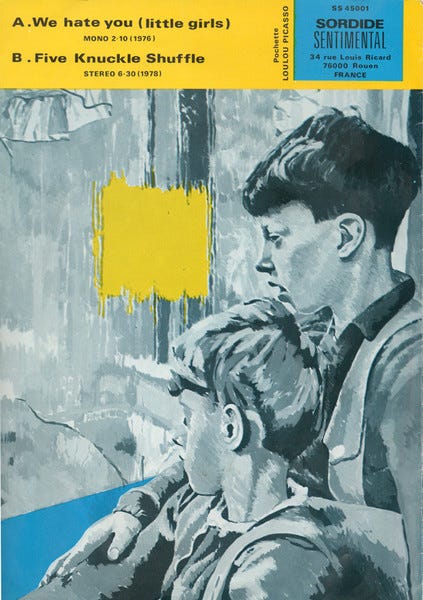

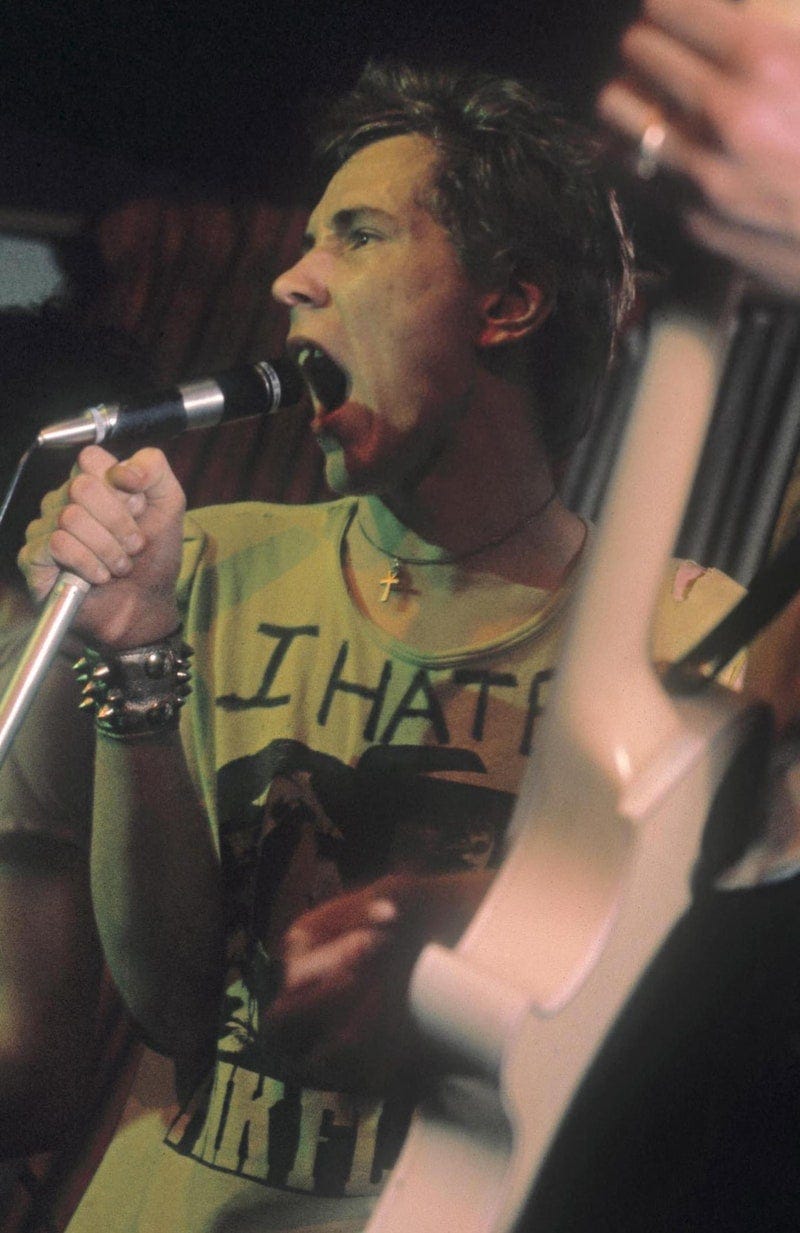

“Hate is such a strong word,” as the saying goes. Even the most incurious, ChatGPT-derived history of alternative culture will present us with a highlight reel of cultural flashpoints who take this as a license to create “strong” work rather than as a fretting rebuke. Johnny Rotten sang that “anger is an energy” and, bedecked in customized t-shirts expressing his hatred of Pink Floyd, launched a thousand similarly inclined ships onto the seas of pop culture. Genesis P. Orridge shrieked “we hate you little girls…with your little curls” over Throbbing Gristle’s caustic spray of atonal electronics, and inadvertently birthed a movement so steeped in psychopathology that s/he would spend a lifetime back-pedaling towards more comfortable hippie origins. The ‘zine culture of the 1990s, ostensibly based in a general goodwill towards those who couldn’t or didn’t know how to mesh with orthodox society, was defined as much by the odd “hate ‘zine” here and there as it was by its more naif and quirky products.

That material so inclined would have a devoted audience is not a seismic shock, though it is fascinating just how unpredictably diverse the audiences were for phenomena which traded in a generalized contempt for the status quo. Disgust and discontent with “the way things are” could make art into a very potent antenna for detecting something redeemable within a decayed society, and could find plenty of adherents where none might have been expected to exist. However, an art of contempt can also be one that serves the status quo - believing it is either fine or trending in the right direction - and therefore art should function to celebrate the consolidation of the true believers and relentlessly mock the regressive idiots who just don’t get it.

To be sure, I myself realized long ago that my musical output (even more so than my written output) was not going to be enjoyed by a mass audience, and that the actual sounds I made had the potential to offend and to make enemies of others, even without obvious polemical themes. Because the particular sound I pursue is “difficult” to those primed to expect something very different, a common assumption is that I’m doing this just for the sake of being a contrary jerk. Though I now expect reactions of that sort as part of the territory, I don’t take any pride in others’ inability to “get” what I’m doing, and I don’t set up some inversion of the prevailing cultural hierarchy wherein I’m proven more “authentic” because of others’ bewilderment and hostility. (It should also be mentioned that plenty of people are, in fact, smart enough to “get it,” but still find it not to their tastes.)

Yet, as I burn off calories wondering how I can make “difficult” work more relatable and even palatable in spite of all historical evidence to the contrary, a not insignificant number of artists and art promoters feel that loudly trumpeted blurts of “IT’S NOT FOR YOU” are a surefire marketing strategy. Here, for example, we have a new translation of the Odyssey, whose supporters have been regularly endorsing on social media with accompaniment by translator Emily Wilson’s portrait. Why is poster “hyuumanatees” convinced this new translation is superior to previous ones? Well, because its source will “make dudebros cry”:

To single out this one comment as being the most significant bellwether of public opinion would be disingenuous, though it certainly is a capable stand-in for scads of identical sentiments. We now find ourselves grazing within a media landscape in which the opening pitches for new works of art, literature, music, etc. regularly claim that their ability to piss off the right constituency is as meritworthy as the work’s actual contents. A salty cascade of “liberal tears” will follow in the wake of a new film documentary, “‘MAGA-tards’ smooth brains” won’t be able to “handle” a compendium of poetry, and so on. In all cases, the assumption seems to be that members of the cultural out-group are irredeemable and not capable of comprehending an art that would foster universally positive values. So, better to just write them off prematurely, and then chortle about how their objections to such treatment are proof of their philistine status.

The increasingly factional nature of “serious” culture, enthusiastically bound up in the task of alienating massive swathes of the Other, may be an outgrowth of the partisan approach that has worked so well in the recent past for the “news” industry. The division of audiences into clear “rooting interests,” a la sports fandom, has translated into more than a few lucrative paydays. Many might also argue that catering to a limited audience, fanatically invested in its personal identity, provides a better and more consistent payoff than courting a much larger, yet much less zealous, “general” audience. Matt Taibbi, in his jeremiad Hate Inc., affirms that this has held true even at a time when independent content creators decreed that the corporate media apparatus was finished as an influential institution:

In 2018, most all the big media companies, despite (or perhaps because of) marked declines in journalistic performance, made buck. The New York Times made a second-quarter profit of $24 million, which as any newspaper person will tell you is good for, well, a newspaper. CBS made a third-quarter profit of $1.24 billion, even after President Les Moonves—the guy who made trouble by admitting Trump was bad for America but good for the “bottom line”—was forced to resign in a #MeToo scandal. At the end of 2018, MSNBC sat in the ratings pole position ahead of Fox for the first time in eighteen years, even as Fox cable itself had record revenues of $1.51 billion.1

This, and other expert analyses like it, seem to prove that there is more to gain by “doubling down” on a built-in audience rather than trying to expand it. So, as the embattled promoter of “serious” culture might conclude, why not port this over to a field of human inquiry that is always despairing its lack of funding?

There is really, when we come down to it, nothing remotely new and therefore nothing “edgy” about this weighing of a cultural product’s value by how well it manages to alienate or repel the Other. One of Robert Cialdini’s key findings on persuasive marketing, i.e. “the strength of [the] social bond is twice as likely to determine product purchase as the product itself,”2 has been famously applied to such case studies of marketing success as the Tupperware party, that multi-level marketing scheme whose particular manipulative genius lay in making the friendly party hostess seem like as much an advocate for the product as the actual salesperson. Cialdini noted how, at these events, “the attraction, the warmth, the security and obligation of friendship are brought to bear on the sales setting,” and how similar forays in manipulating social bonds could inspire the purchase of a product sight unseen, provided a friend was seen as its sincere advocate. These strategies apply just as readily to products which re-affirm one’s existing social bonds by promising to do demoralize a cultural enemy.

Now, in his examination of the Tupperware party phenomenon, Cialdini also names a certain devious operator - the sinister-sounding “compliance professional” - who deserves some credit for identifying and exploiting such quirks in the psychology of persuasion. I find it equally incredible and depressing that, when I describe the activities of such a type to a known social / political partisan, they will instantly assume that these cynical mind-masters are used solely in the employ of their enemies. The truth, sketched to a believable degree in classics like Manufacturing Consent, is that the media and cultural equivalents of “compliance professionals” set the acceptable bounds of discourse for both contradictory poles (and there are almost always only two).

This is akin to having a handful of candidates for public office propped up via various insider interests, and then convincing the electorate that they, “the people,” are the masters of their democratic fate since they may choose between a few candidates pre-screened by the entrenched and un-elected bureaucracy. A given cultural faction will bear witness to a new artwork that seems to be done by “one of us,” and will rejoice that they have another brave knight to sally forth into the fray of the Culture War for them, but they will less often question that the very terms of that Culture War have been dictated to them. For some, the truth that one’s entire cultural identity may have been stage-managed rather than organically, independently developed is a drink too bitter to the taste. Yet, if we continue to believe in things such as a “true” or “authentic” self, it’s a medicine that needs to be taken sooner or later.

The “compliance professionals” aiding this simplification of human identity have, I believe, intuited that ginning up intramural hatred satisfies an innate need for simple solutions to complex problems. It also likely recognizes that, unless such simple binary formulations are proposed, the restless human spirit will eventually gravitate towards a questioning of more complex issues, e.g. the opaque nature of the alliances between corporations and federal government. A completely dichotomous relationship between two cultural forces, in which one is always right and can re-assess some small plank of the platform only at the great reputational cost of social alienation, is a surefire way to allow bi-partisan abuses of power and influence among the predator class to go unexamined or under-examined.

Moreover, reducing complex human experience to an all-or-nothing bloodsport will, over time, result in the progressive degradation of cultural or artistic content itself. It is far easier, in my estimation, to make a cultural weapon that demoralizes an enemy or distracts it from more pressing matters, than to craft something which reveals what we have within us all and then propose how we make the best use of it. Works made with the primary intent of drawing a line in the sand between an allied culture and an enemy culture will by necessity be more monotonously aggressive, less capable of nuance or subtlety, and far less capable of encouraging self-reflection or enhancing a sense of personal agency.

Art fashioned as such will just be, in essence, pointless: it will merely be fulfilling the same social functions as the already existing news media. It will trade in moronic sentiments such as the genre of commentary that Taibbi accurately pegged as “this bad thing that just happened is someone else’s fault” (and, by extension, nothing is “everybody’s fault”). Without the ability to view art as a tool for rigorous self-interrogation, we will simply consign it to the same fate Taibbi reserves for that type of story: it will “narrow your mental horizons”. The artistic cultivation of wonderment / awe, which itself clarifies what is valuable in life and motivates us to seek and preserve these values, cannot peacefully co-exist with an art bound up in the belief that the “big questions” of life have all been satisfactorily answered, and now it’s just a matter of using art as a kind of enforcement mechanism.

Once the mental horizons have been sufficiently narrowed, though, the artist then finds himself or herself in an increasingly difficult situation when it comes time to expand them again. Sudden epiphanies or changes of heart on inflammatory issues will be season as treasonous by an audience thusly conditioned, as will even mild admissions of specific agreements or commonalities with the enemy (“Hitler put on his pants one leg at a time, too,” etc.) Those who would have had the potential to be society’s most trenchant critics will be reduced to the role of sniveling tattletales, in the process relegating the aesthetic dimension of their work almost as an afterthought.

As we bear witness to signal events like Western governments crumbling in scandal and disgrace, I am optimistic that we are going to see a global re-alignment of priorities not beholden to historical social models and to simplistic, static conceptions of human desiderata. Key to this catabolization will be a rejection of the falsehood that the socio-cultural pie can be split cleanly between servings of ideologically pure “Left” and “Right.” With that, I hope, will come a renewed emphasis on art’s deeply personal nature and a focus on those experiences that are uniquely one’s own, even though its products may bear superficial or even profound resemblance to the experience of others.

For Heidegger, gaining knowledge of one’s communal history and of the speculative possibilities for one’s community were essential to the creative process, described in Being and Time with such poetic sobriquets as “resolute rapture”. True to the title of Heidegger’s magnum opus, authenticity meant not merely “being” but being in time: to be cognizant of the temporal dimension was an act of ek stasis, standing outside the self to understand the significance of history and the possibility of a future. Through these processes, we may even bring the very community we are part of into existence: to briefly flashback to some of the cultural phenomena mentioned at the outset, even a punk band nihilistically sneering “no future” somehow managed to (for better or worse) create a multi-generational community unmistakably different from other contemporaneous subcultures.

Sure, they had more than enough hate to dispense to the public, but that hate and that despairing of the future sprang from general discontent with people’s voluntary decisions to reduce their developmental possibilities. I would, without hesitation, claim their own alienation derived from a fatigue with the false security of in-group / out-group lifestyle, and its belief that mere distinction from adversarial cultures amounted to some sort of superior insight. Johnny Rotten seemed to see where this was all headed early in the game - a culture confrontational enough to reject particular manifestations of conformity, and assume that this was what “everyone else” did, but never bold enough to question the bases for conformity itself:

The one thing that used to piss me most about the Sex Pistols was our audience all turning up in identically cloned punk outfits. That really defeated the point. There was no way I was going to give them a good time for that, because it showed no sense of individuality or understanding of what we were doing. We weren’t about uniformity.3

Art and culture stand now at a crossroads. These forces can choose to become an annex of the media which already exist to pimp the lie of a perfect, Boolean division of sociopolitical values, and artists can eagerly consort with “compliance professionals” (or become them outright). On the other hand, they can re-establish themselves as forces that see tribal inside-outside distinctions as an impediment to the expansion and refinement of all that is truly worthwhile. Whether or not the latter choice would “make dudebros cry” has yet to be seen, but I can assure you that stoking their hate and fear doesn’t count for much at all.

Taibbi, M. (2019). Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another. New York / London: OR Books / Counterpoint Press

Cialdini, R. (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. London / New York: Harper Collins.

Lydon, J. (1994) Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. New York: Picador.