As this past U.S. election cycle has affirmed, our electoral politics have devolved into a zero-sum bloodsport. The days of near-universal consensus as to the nation’s purpose, and the 49-state landslide victories expected to follow on the heels of that consensus, are long behind us: the country appears perfectly partitioned into one half “red team” and one half “blue team” voters, with an alarming level of incompatibility in the policy goals these “teams” hold dear (to say nothing of the means proposed to achieve these goals). What follows is my humble attempt to suggest how we live with this situation, and how we can avoid the worst-case scenarios.

First, let us concede that things are not as horrible as you have been led to believe by our corporate media apparatus. We must remember that, as an undeclared yet fairly obvious propaganda wing of the political establishment, they are under no obligation to really speak the truth, nor do they need to fear accountability to the same degree as us lowly serfs. Thusly emboldened, they have recklessly preyed on humans’ inherent negativity bias, and likely know that doing so leads to an increase in impulsive clicks and views. More importantly, a state of unrelieved anxiety or terror confers legitimacy upon their State sponsors (who will be suggested as the solution to crises of their own creation). In brief, you have been fed a wretched diet of distortions and exaggerations from this machine: proceed from the assumption they are wrong in their claims until proven otherwise, and you are already on the way to regaining your sanity.

I’d also recommend a simple long-term experiment for anyone who regularly consumes such media: upon reaching a major cultural inflection point such as the current one, make a thorough list of catastrophic events that you fear will come to pass over the next few months or years. Return to check these off each time one of these catastrophes does play out as you imagined it. I think you will find there will be a fairly low “hit rate” for the most terrifying outcomes (a fear of being herded into Trump-built extermination camps is one I am now hearing a lot of), and that events of a genuinely catastrophic nature will not even be the ones that were predicted.

I cannot emphasize enough the damage that comes from routinely taking the crisis merchants at their word, particularly when even remedial exercises such as the above will reveal the lack of seriousness at the core of their enterprise. Have you noticed, for example, the genial, un-terrified way in which the recently defeated Biden-Harris team greeted the victory of the man who they had been calling a Hitlerian fascist for months prior? Either they were completely fine with the eventuality that fascism would triumph, or they are fundamentally un-serious and have no real conviction animating their alarmist rhetoric. Given all available evidence, I assume the latter for now.

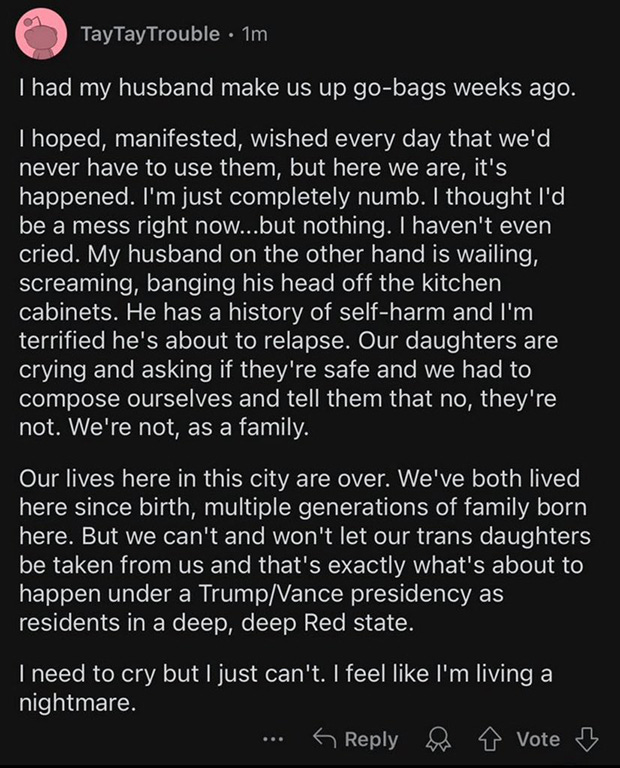

Therefore, I urge concerned people to avoid the pathological behavior of the kind described in this now viral post:

If you are feeling distress of this level over anything other than an imminent, manifest threat to your safety, I strongly encourage you to stop reading this and to immediately dial 988 for free counseling. And this brings us to another pernicious effect of the “official” crisis-stoking media, which is its trickle-down of terror to independent creators on social media and “IRL.” This became highly evident to an increasing number of individuals during the recent COVID lockdowns, when completely partisan media and completely impenetrable social information bubbles went un-challenged by the less directed information flow that one encounters simply by going to work, nursing beers at the pub, etc. etc.

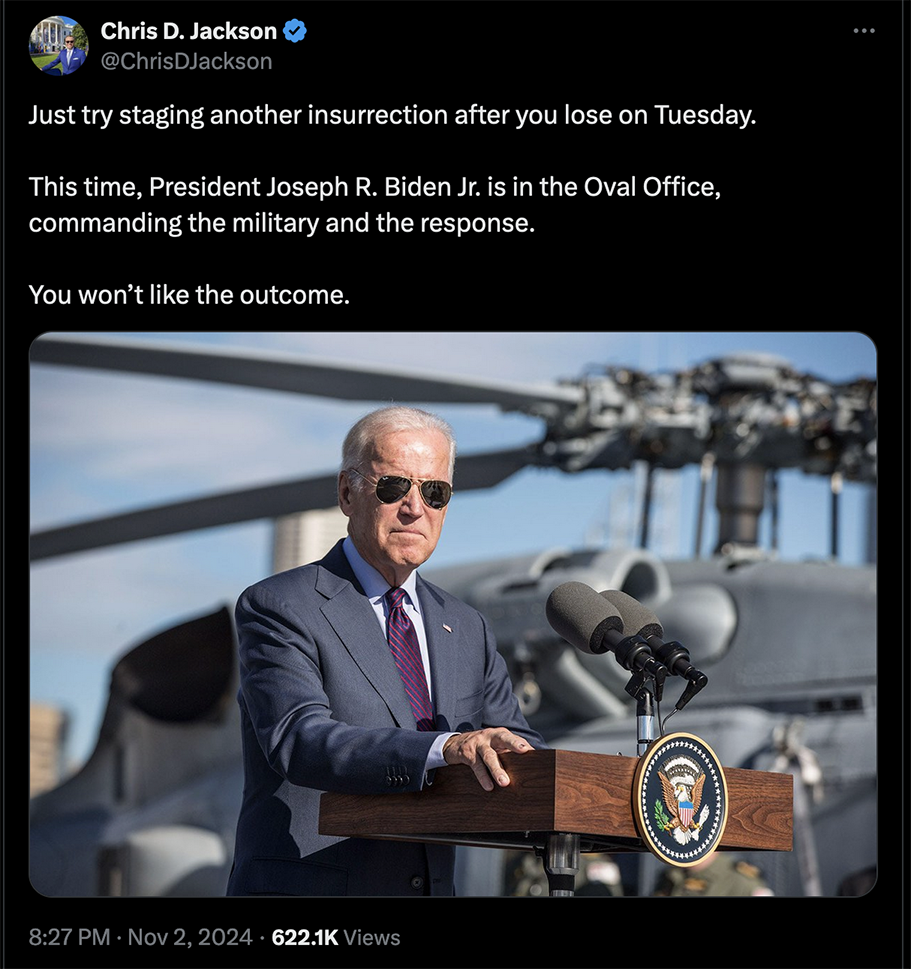

For those who are not driven to suicidal despair by the Manichean narrative peddled by the media, there will be others who have their sense of determination and personal agency increased by the crisis, and who will find new meaning in identifying an enemy to be destroyed. Open calls for military action against roughly one half of the populace have been a social media fixture since at least 2016, and they are truly one of the worst symptoms of our national disease of political partisanship. Thousands of social media posts could be presented as evidence of this nauseating trend, but a recent one should act as a satisfactory stand-in for all of them:

These types of provocations, and the responses to them, are extremely formulaic and predictable in their content: the outgoing president himself previously egged on would-be insurrectionists with a repeated claim that their “AR-15s” are no match against “F-15s”, and, like clockwork, countless reminders of U.S. military defeats in Vietnam and Afghanistan follow. Perhaps it is the very predictability of these kinds of exchanges, and, again, the hermetically sealed “information bubbles” which encourage them, that lead partisans to have a good deal of confidence in how a full-scale American civil war would pan out. The eagerness of an increasing number of citizens to participate in such a thing should be unsettling to everyone, and vehemently rejected on a number of different grounds.

Firstly, a civil war will not be brief. Anyone suggesting as much needs to revisit the build-up to the first World War, and the disastrous assumptions that it would only last a few months (due, among other reasons given, to the supposed inability of the international financial system to support a lengthier conflict). Even with tactical blueprints such as the “Schlieffen Plan” in place to ensure a brief and decisive war, WWI became the classic example of enormously costly attrition warfare. Like the Spanish Civil War that would follow in the 1930s, financial exhaustion did not mean the cessation of hostilities: other countries could provide the principal combatants with the war material to allow the bloodshed to go on interminably.

This leads us to the realization that a civil war will also not be predictable, by any stretch of the imagination. Violent conflicts on a national scale tend to spiral out of the control of their planners, and to stoke a variety of secondary and tertiary disputes; the atmosphere of violent chaos opened up by the primary conflict allows for otherwise unrelated grudges and unresolved disputes to become explosive “kinetic” conflicts. It becomes even more difficult to divine the future once the conflict goes international, and the now Dis-united States become the stage for a wider war of ideologies. It’s hard to envision a scenario whereby all the other major powers stay neutral, given the bountiful spoils that they’d be able to enjoy if they place their bets on the winning side.

A civil war will, lastly, be cruel and traumatizing beyond anything most of us have experienced. I used to believe that a-historical, postmodern Americans would be incapable of matching the brutality of, say, combatants in the former Yugoslavian republics fueled by centuries-old hatreds, but given the social trends I’ve shared above, I am now not so sure. We now throw around terms of dehumanization with an increasingly disturbing sense of casualness: right-wing social media accounts are not entirely joking when posting such banalities as “commies aren’t human,” and leftie posters have vastly expanded the menagerie of offenders whom they consider to be irredeemable Nazi monsters. It is poignant that one of the ethical foundations uniting us - the belief that it is wrong to kill another human - still becomes a partisan issue, as we all have very different ideas of what rises to the level of human.

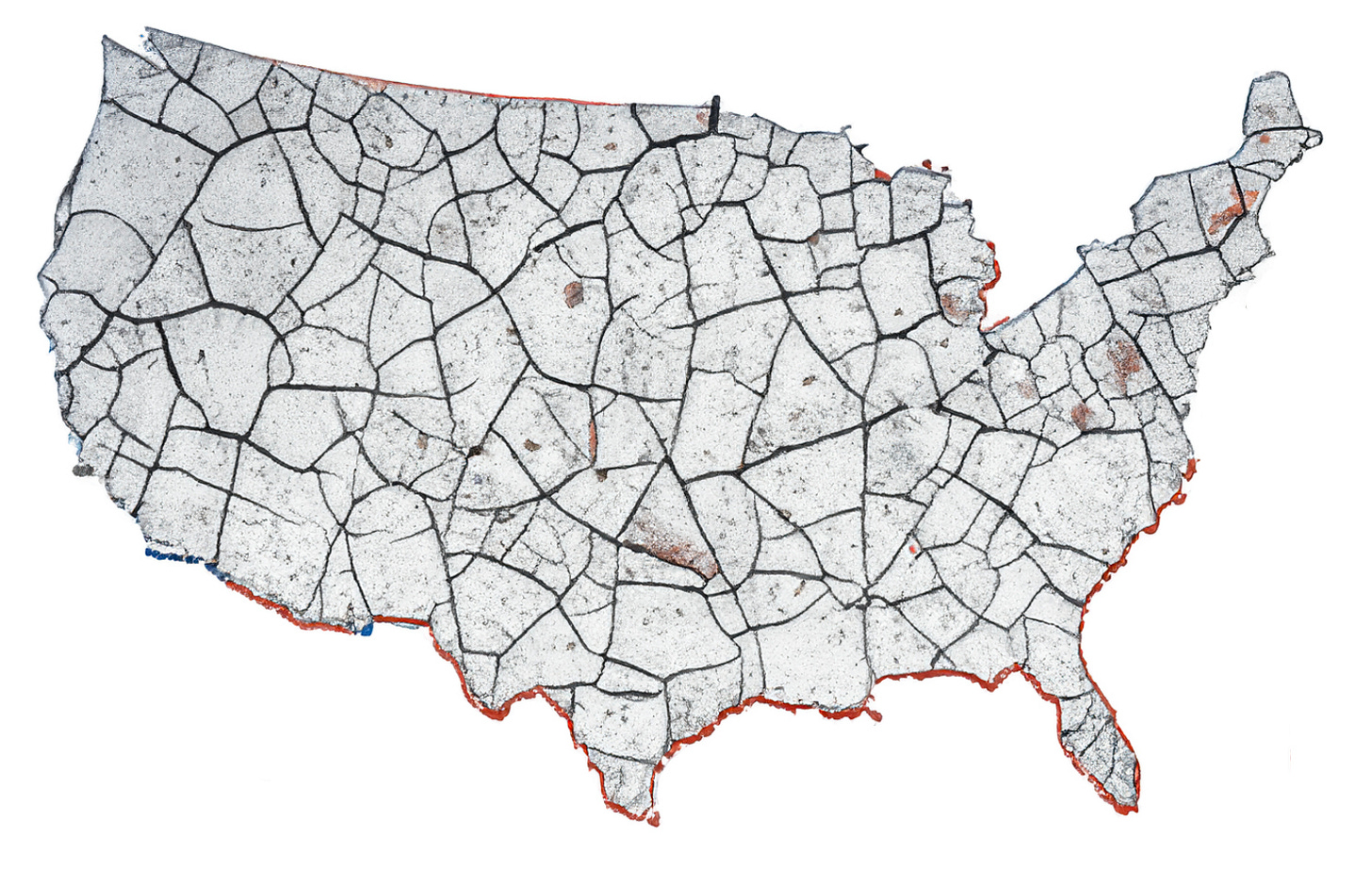

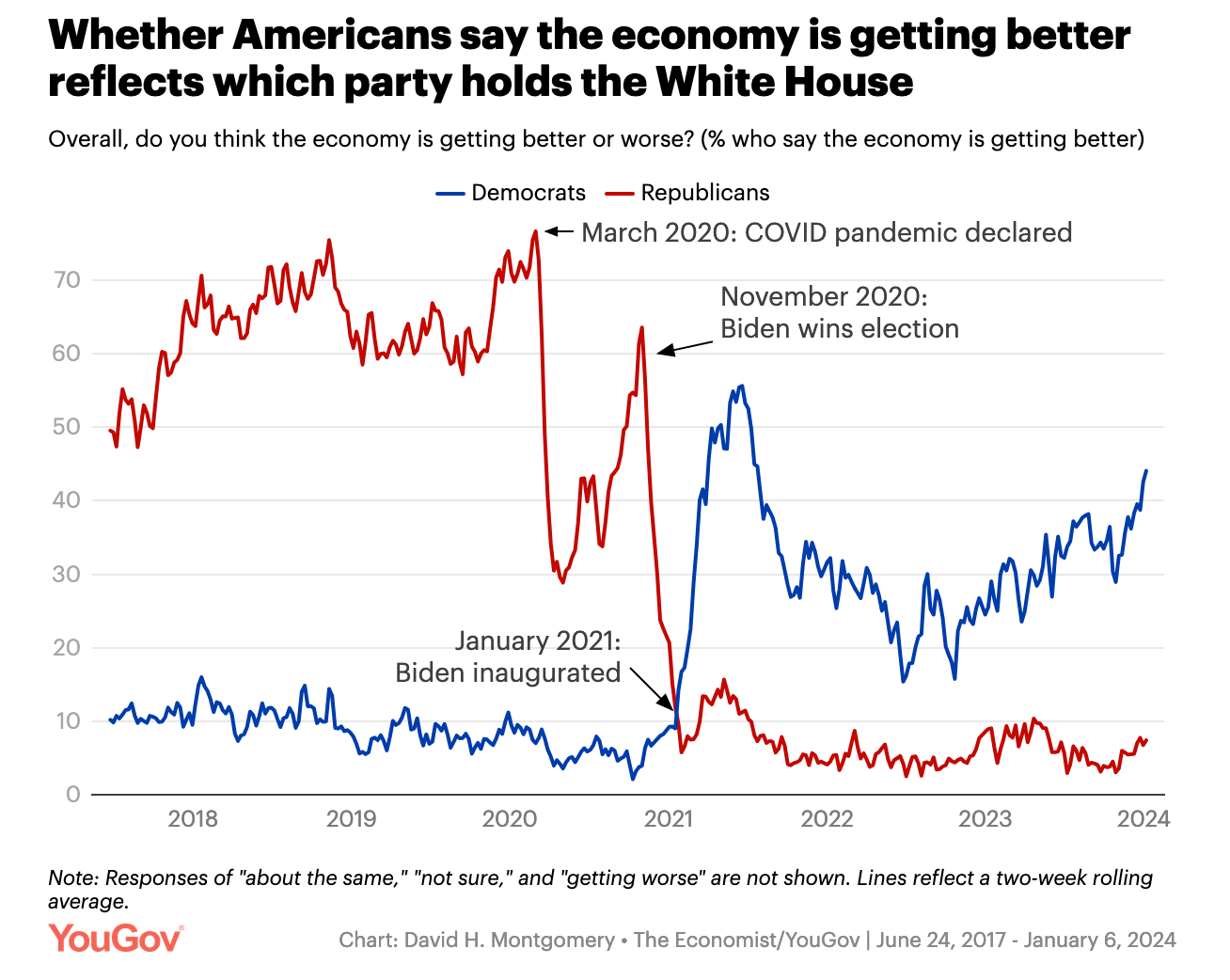

So let’s just assume, for the time being, that there is never going to be any reconciliation between Team Red and Team Blue without military involvement. Let’s assume that these two halves will continue to buy into the media oversimplification of their complex ideals, and will continue to general elections as a vehicle to decide which 49% of the electorate will be punished and oppressed for a minimum of four years. As demonstrated by recent survey results on the state of the economy, all these attitudes are reflected in the finding that national feelings of optimism or negativity depend upon whether or not one’s party is in power:

Does all this necessarily have to lead to war? I don’t believe so. Even recent examples such as Brexit, whatever one’s opinion on it, indicate that disassociating from a larger union can happen via democratic referendum rather than organized violence. The alternative of a mutually agreed “national divorce” into multiple sovereign nations is not going to be equally pleasing to everyone, but it is surely preferable to the privations of war, or just more of the widespread, normalized state of unrelieved anxiety over future election outcomes.

In the version of history proposed by textbooks in U.S. public schools, the desire of individual states to secede from the “sacred union” is forever tarnished with some desire to preserve the institution of slavery. Nevertheless, we are already seeing something like an informal and mutually agreed dismantling of this union. Ideological segregation in the U.S. has expanded dramatically in the 21st century, with the now rapid increase in “work from home” and other socio-economic phenomena creating an environment where one can more easily move to a state that matches one’s own belief system (although the increased “reddening” of progressive California is a weird counter to a clean narrative in which that state represents one polar extreme, and Florida is the apex of conservatism).

We can then “drill down” from the state level to individual communities and see more of the same. Neighborhoods dominated with patriotic regalia and U.S. Marine Corps flags will be neatly partitioned from neighborhoods lined with houses displaying the “In This House, We Believe…” sign in their front yards. Individual restaurants, cafes, and retail establishments will make similar overtures to ensure that they serve a clientele that almost exclusively shares their political concerns. If this is to be the way that the politically involved choose to organize their lives, it seems more likely than not that a peaceable separation of the union would be possible: we are practically there already.

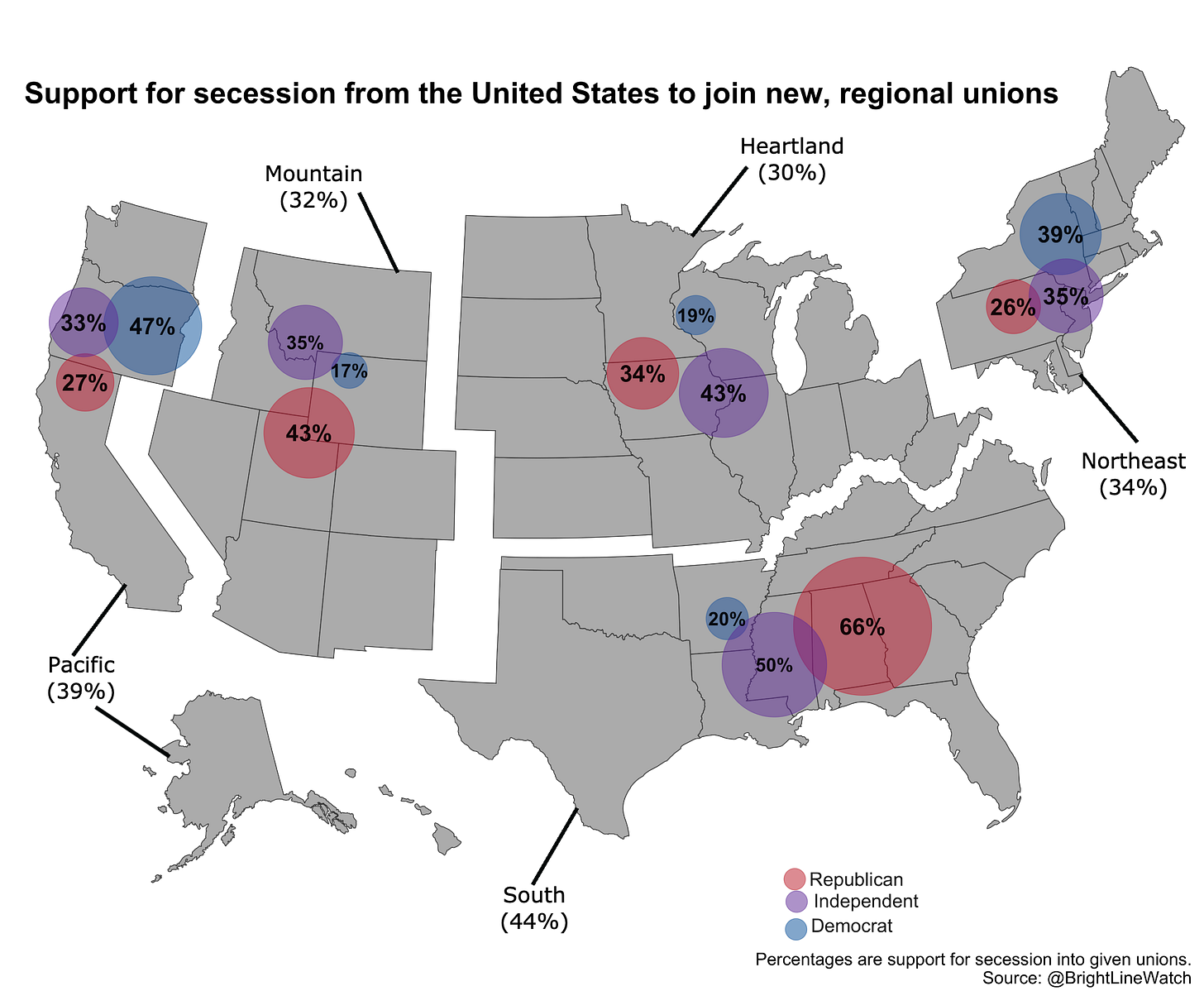

A Bright Line survey conducted earlier in the Biden presidency revealed, to a surprising degree, that “levels of expressed support for secession are arrestingly high” and furthermore that this support was not exclusively limited to the Southern conservatives normally assumed to be its greatest champions. Two full years before the first election of Donald Trump, things were already trending in this direction: 29.7% of surveyed Republicans spoke favorably of some form of secession compared with 21% of Democrats. What was once a “fringe” idea is gradually being spoken of as an increasingly plausible solution to a myriad of social problems, and the number of movements based on states’ autonomy from federal authority is only growing.

As Americans (and I would apply this to other nation-states as well), I think we need to take a resolute step back from the Hobbesian idea that a central power is the guarantor of our rights and liberties. I think we would do well to consider the truth of the matter; that such central authorities have historically been preceded by complex webs of social interaction limiting the extent of their powers. I would also concur with what anarchist thinkers around the time of the Spanish Civil War contended, i.e. “there was no hope of justice in any society unless it was first achieved among small groups of men.”1 The more expansive a state becomes, the less ability we have to dictate things at what Kirkpatrick Sale famously called the “human scale,” and the more the role of government turns to the enforced standardization of all areas of life.

Super-states like the United States, or what we might more properly call “empires,” are not the blinding eternal flame that we like to think we are: Sale notes, for example, that “the Roman empire, so often celebrated by historians, had an effective lifetime of only about 200 years” and that the Pax Brittanica of the British Empire, “the largest imperium ever known,” had an even shorter duration, lasting roughly from the 1815 colonization of Malta and Ceylon to the “transition to Commonwealth in 1931.”2 Sale subsequently notes that, even within these vast empires, most decisions of import were still happening at the community level:

Nations themselves were simply non-existent through the greater part of history, the notion of separate racial and ethnic groupings finding political expression through a single government being regarded as impractical if not absurd. The very idea of nationalism, in fact, far from being the universal and everlasting notion we sometimes assume it to be, is of comparatively recent origin, and the word does not even enter the English language until the middle of the nineteenth century.

While I do not want to make a fallacious argument that things of more recent invention are less valuable, at the same time we should acknowledge that nation-states are much more precarious than we are led to believe. Nor (and here I can finally say how this all relates to the arts somehow) are increasingly centralized bastions of “bigness” necessary to inculcate astonishing outbreaks of creativity: Sale relates how “the Florence of Boticelli and Leonardo” had only 40,000 souls contained within, and “The extraordinary medieval painters of Northern Europe flourished in a region where most cities were under 15,000”.

Giant nation-states do have their own innovations, but these tend more often to be instruments of control, coercion and war. It seems that not even a nation ostensibly founded on principles of liberty and self-determination can avoid using these tools once it operates on the scale of a global power. In fact, the “civil war” discourse we now deal with is a predictable feature of a society whose central authority requires the threat of violence to shape the behaviors of an historically diverse electorate: there is a kind of “learned helplessness” reaction instilled in us that makes punitive violence seem like the inevitable means of resolving complex issues. We would be better served, I think, by simply admitting that the innumerable affinity groups forming the union would be happier in autonomous regions subject to their own laws, and free to follow their own ways of life without causing offense to others.

This, to my mind, feels healthier in the long run than living in constant fear of a majority vote nullifying rights that have taken decades or centuries to be enumerated. Nor does a majority of the “popular vote” even imply the ethical rightness of some custom or institution: would we really be “respecting the will of the majority” if it voted tomorrow to re-institute slavery across the United States, or to institute the death penalty for trivial offenses? In such scenarios, and even less apocalyptic ones, minorities would be so alienated that it would hardly matter if they were living in a democracy rather than under the rule of a single tyrant. As John Calhoun argued, “The numerical majority is as truly a single power—and excludes the negative as completely as the absolute government of one or a few.”3

So, in a scenario where the United States were allowed a peaceful and mutually recognized disintegration, I am not naive enough to believe that everyone would get everything they want out of this arrangement: but we would have far fewer permanent minorities who, excluded by majority opinion, are getting nothing that they want. The more embittered and humiliated citizens who feel this sense of complete civic exclusion, the more will feel they have nothing to lose, and the more who will turn to violence merely to restore some sense of lost dignity. Once that spark of conflict inevitably transforms into a nation-wide inferno, nobody will win.

Thomas, H. (2001). The Spanish Civil War. New York: The Modern Library / Random House.

Sale, K. (1980). Human Scale. New York: Coward, McMann and Geoghegan.

Calhoun, J.C. (1953). Disquisitions on Government and Selections from the Discourses. Indianapolis, IN & New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co.