A little while ago, somebody joked that a lot of my work on this message-in-a-bottle Substack column has a strong odor of “life coaching” to it. Fair enough - as a “designer” of sound, I suppose that I follow the definition of design as the change from an actual state to a preferred state, and that convincing others of this preferred state’s benefits could be described as a “self-help” service of sorts. Yet this is a term brimful of negative connotations, as even the mildly skeptical regard “self-help” culture as one that encourages acceptance of all-encompassing “trust the plan” panaceas at the expense of real critical inquiry. I myself have attempted to stay as far away as possible from post-“Oprah” wellness cultures based on the central conceit that the “kingdom of God is within you” (Oprah, you see, has the “God force” within her and counsels us that “once you tap into that, you can do anything”).1

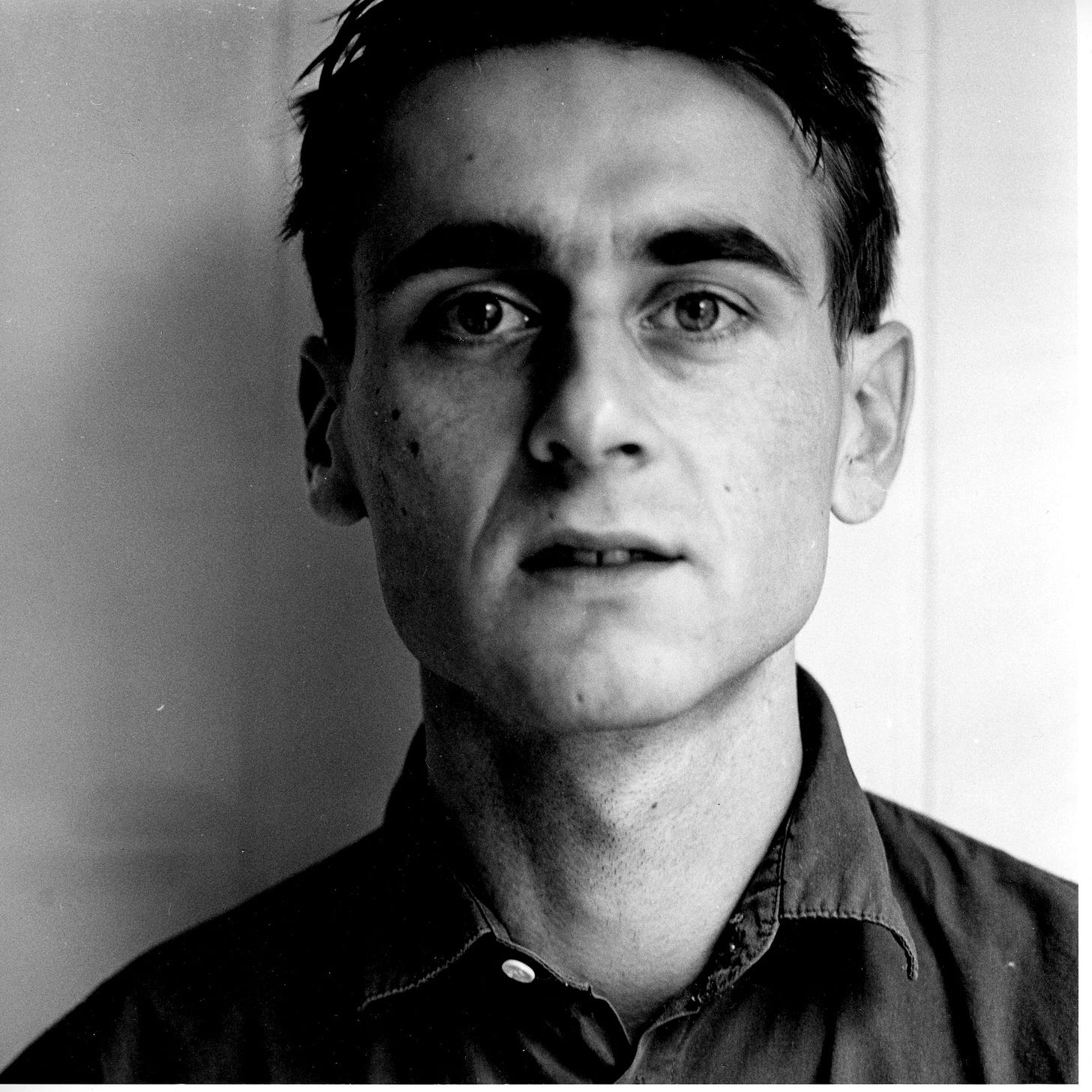

I’d tend towards the opposite stance, that the fixation on an ideal self is at the heart of much that is wrong with modernity. Yet it’s clear to me that the subculture I inhabit does need some form of external guidance: it is riddled with deep psychic wounds, its ranks plagued by below-average life expectancy and by deaths of despair. It is in desperate need of something more inspiring than practiced (but generally insincere) disaffection and trendy necrophilic theorizing which, on the whole, is as useful to the hopeless as chiding them with “it can always get worse”. Despite the nauseating fog of melancholy that eats away at our collective resolve, many of us are encouraged (and financially incentivized) to serve our audience work animated by trivial themes or pedantic challenges, when the focus should be upon providing an affirmative answer to Camus’ one true philosophical problem: whether or not life is worth living. I know of at least one person who actively helped me to do just that: the nomadic, psycho-acoustic composer Zbigniew Karkowski (1958-2013).

Making a conventional background sketch of a peripatetic individual like Karkowski is not clean and easy, and, in keeping with his often contradictory nature, it is more illuminating to begin at the end of his journey. In 2013, in the throes of terminal cancer, he underwent what must have been a severely painful and almost day-long journey from Europe to the heart of the Amazon, where he would be treated by a local shaman-healer. Perhaps understanding the slim chance of this last-ditch effort succeeding, he had also requested to have his remains left in the jungle for the animals to devour (reminding me of the old Taoist saying about letting the birds have a meal as long as the worms were also being well fed). This episode, in all its romantic boldness, was an appropriate coda to a life whose message, for those willing to hear it, was one of reverence to something greater than the atomized self. His creative actions prior to his death refused to partition the world between this internal self and an “external” environment that serves no other purpose than to corrupt this pure entity.

In a brief but action-packed manifesto titled “The Method of Science, The Aim of Religion”, Karkowski rejected the idea of the artist as a purely autonomous being alone with his or her “truth”, and unequivocally stated his adherence to a belief that “all the individuals who have ever created something of value did so not as inventors but as catalysts of existing forces”. The manifesto title hinted at repairing the state of art bemoaned by Donald Kuspit (i.e. “modern art is an aesthetic failure, for the split between an art of reason and an art of sense grows greater and greater…”)2 Against this, explicitly Karkowksi himself proposed a “music directed not to the intellect, but to all the senses…music whose only function is the total integration of those sacred energies and forces that exist latent in all of us,” though I am certain he knew that sensory information was a necessary prerequisite to what we call intellect, and that he also enjoyed using the technological products of that intellect to make this music which revitalized the senses.

And what about the content of that music, exactly? With multiple references having just been made towards “the spiritual” or “the sacred,” neophytes might expect Karkowski’s output to approximate the other silly gestures that musicians often make in an effort to appear as authorities on esoteric subjects. I can assure you this is neither some dopey neo-exotica nor heavy metal occult gimmickry: in fact, Karkowski’s sonic art exceeded the sheer aural and physical impact of the latter, and the ecstatic potential of the former, without any reliance on a theatrical presentation or “lifestyle” affectations. He intended for his output to be felt more than heard, and knew that the extreme volume required by this process could, again, effectively expand the whole human sensorium. For the sake of journalistic convenience and / or laziness, his work was generally tagged as “noise,” but this is a term already too tainted by an association with temporally limited fashions. I would liken it more to something like Giacinto Scelsi’s most intense symphonic work (another artist who felt himself to be a “messenger” rather than an autonomous composer). In fact I feel that this expert description of Scelsi’s compositions by Gianmario Borio could be re-applied to Karkowski’s work with no alteration other than the composer’s name:

[Scelsi] showed that the range of usable material is nowhere near exhausted, that a restriction of the point of view—to an interval or a sound—could reveal unimagined creative possibilities. Two complementary points of view entered the public conscience: that the single sound is not a uniform but a complex phenomenon and, inversely, that a complex composition can be presented as a single sound. But Scelsi’s work has also made clear an ideal often aspired to by the serial and informal avant-garde: the abolition of hierarchies among the parameters. The distinction between pitch and duration as structural parameters and timbre as well as dynamics as secondary parameters was overcome by Scelsi through a reversal process that relocated all “peripheral” dimensions to the center of the compositional work.3

I believe Karkowski effected very much the same “reversal” process, disregarding the need for tonal centers or recognizable song-form, while allowing any formerly ephemeral or marginal elements of sound to steal the limelight, then mass together and practically explode into the listener’s consciousness. In so doing, he had the template in place for a career-long project of demonstrating that the transformative potential of our sensory perception was, like Scelsi’s “usable material,

also far from exhausted.

Another function of the focus on the physiological effect of intensity and volume was to show how we human listeners are not nearly as passive as we believe ourselves to be. When confronted with the so-called wall of sound, our perceptual apparatus reacts to the monotony by realizing details that may not have been present in the composition itself: we begin hearing overtones and other previously hidden features, to say nothing of our abilities to inject apophenia into the mix (attempting to domesticate the flood of completely abstract data by adding our own subjective meanings to it).

Though I could make my own recommendations for points of entry, Karkowski’s massive discography isn’t marked by any “canonical” works: everyone will have their personal favorites based on relatively random factors such as the circumstances in which this sound was introduced to them. It is, as a whole, non-conceptual in its striving to simply be this Scelsi-an “…sound matter that approach[es] states and processes of nature.”4 Sound, the result of the interaction of the parameters, is at the center of this work.” Like seasoned jazz hands who also used music as a form of psycho-spiritual transport rather than as a conceptual framing device, Karkowski was an avid collaborator, and he regularly eschewed hierarchical arrangements within this social sphere.

This brings us at last to Karkowski as a kind of unwitting “self-help” or “self-empowerment” coach. Again I have to emphasize that Zbigniew would not have wanted anything to do with methods intended to “justify” one’s self, or to rationalize away one’s recurring mistakes and legitimately harmful behaviors. Much more in keeping with Zen or Taoist traditions (and such are hinted at in Karkowski track titles like “Doing by Not Doing”), Zbigniew’s sonic actions pointed towards a kind of “positive diminution” of the self that is, paradoxically, a helpful process in truly empowering the individual to expand. This was, again, a refutation of those aforementioned systems of self-actualization that encouraged the maintenance of a pure, inner self against the influence of the external world. It could be called a quest for authenticity, but only in the pre-“self empowerment” culture sense that Charles Guignon relates here:

The conception of the self as inextricably tied to a wider context also makes possible the ancient virtue of reverence, a way of experiencing things that includes an awareness of the intricate interwovenness of all reality, the dependence of each person on something greater than him- or herself, the consequent sense of human limitations that comes from such an awareness, and an experience of awe before the forces that lie outside human control.5

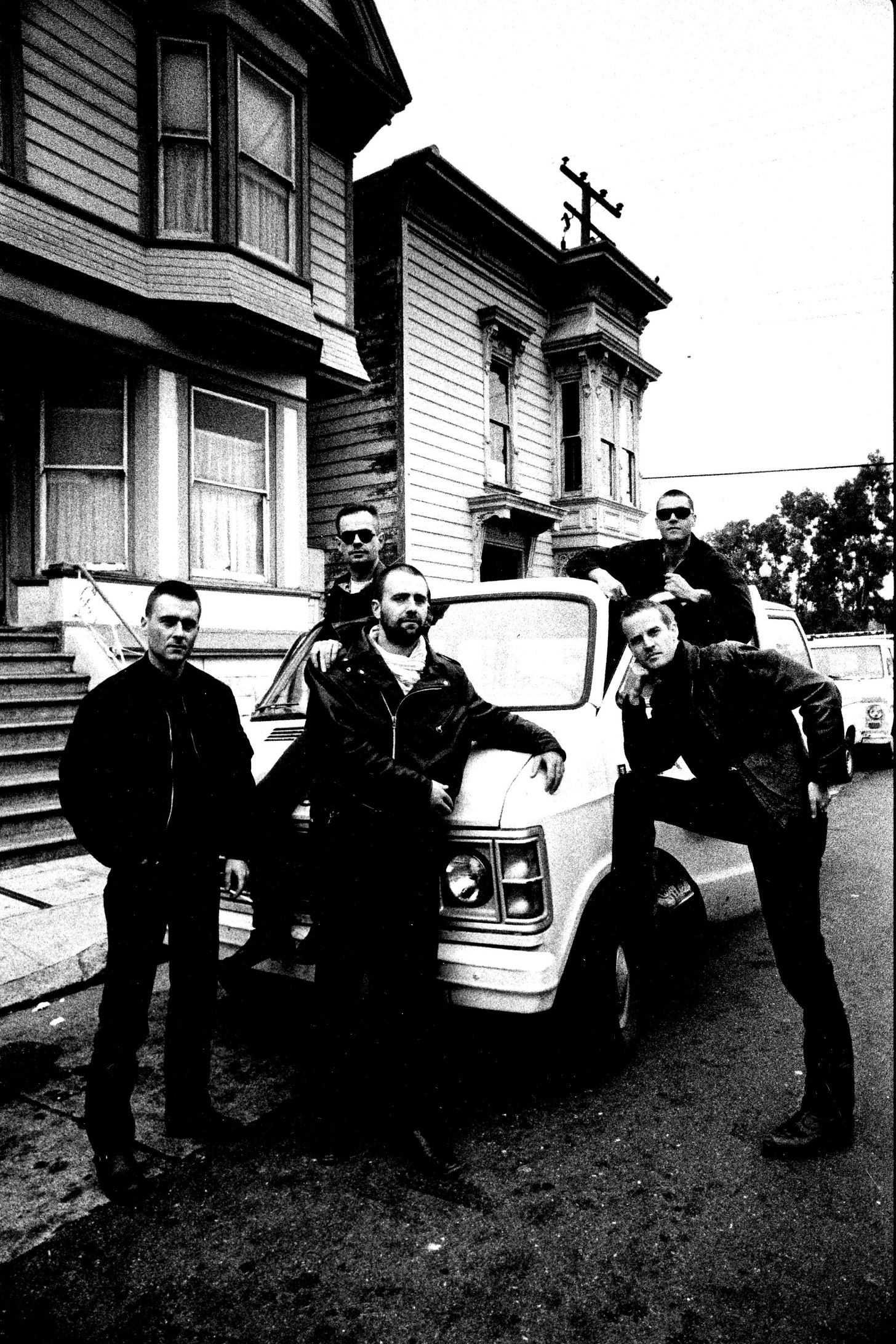

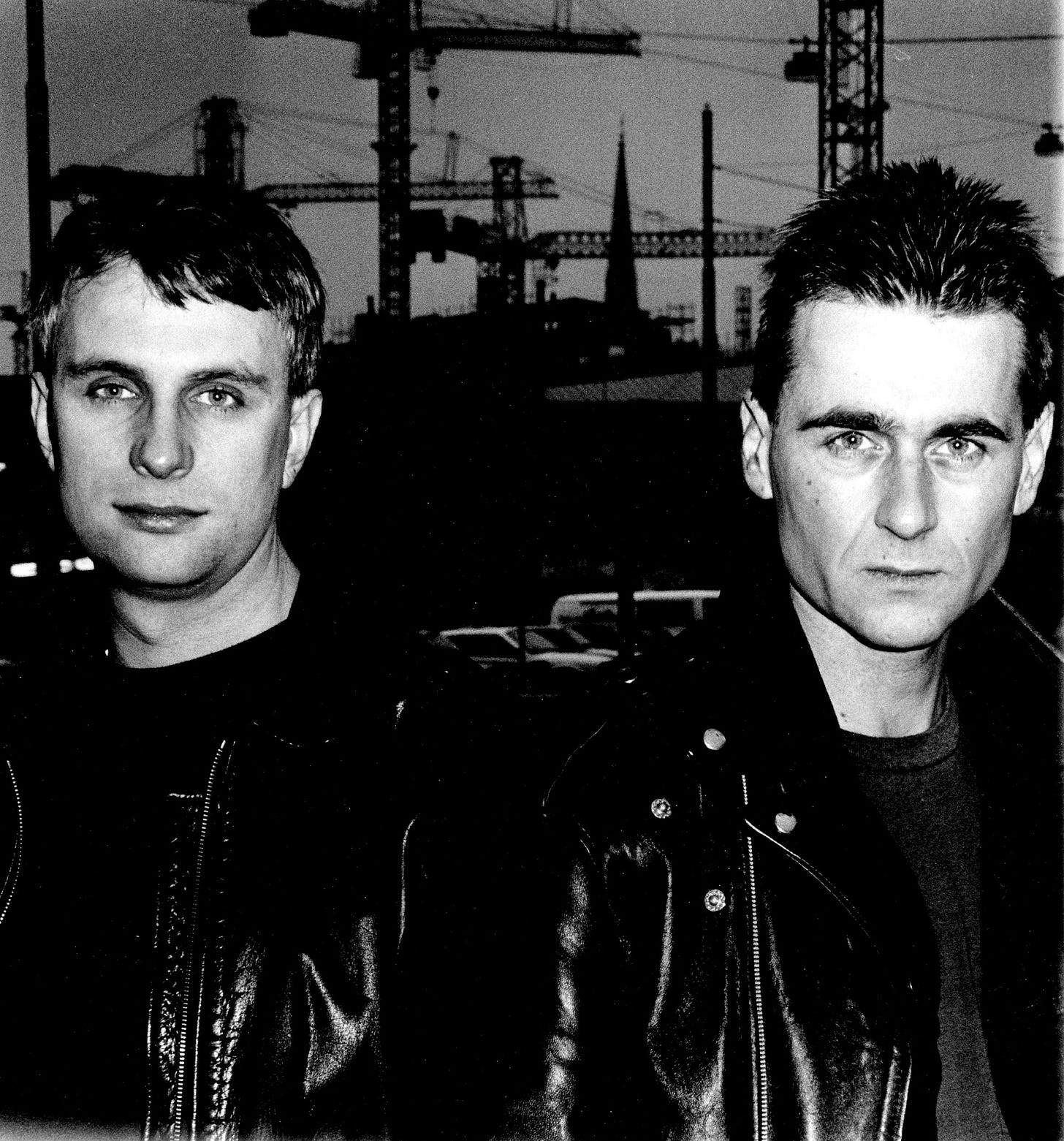

Having noted this, there was another interesting aspect to the social extension of Karkowski’s personal aesthetic. He did have a legitimate “serious music” pedigree of sorts: according to one curriculum vitae published in the august Computer Music Journal, he “studied composition at the State College of Music in Gothenburg, Sweden, aesthetics of modern music at the University of Gothenburg’s Department of Musicology, and computer music at the Chalmers University of Technology.” His teachers included heavyweights Iannis Xenakis, Olivier Messiaen, and Pierre Boulez. Unlike numerous others boasting that background, though, he had no allergy to working with those who were active in “d.i.y.” culture, and often reminded us that the ideas bubbling up from this culture could equal the output of the academically trained. Not surprisingly, his efforts to promote such individuals weren’t always reciprocated (as when he walked off of the “digital musics prize” jury at the Ars Electronica festival after his insistence on “blind” judging of the entries, i.e. with no foreknowledge of the creators’ biographical details, was ignored).

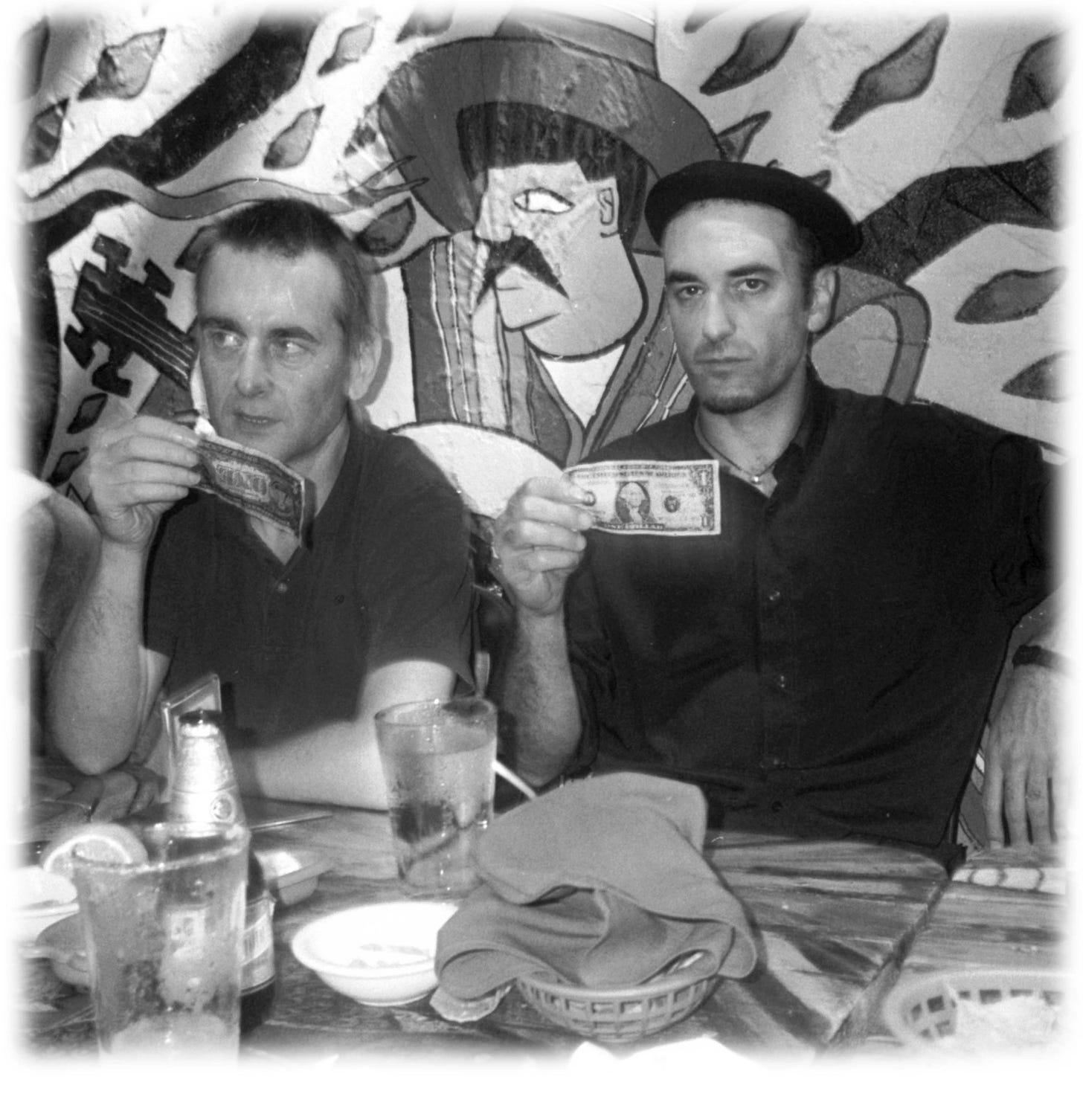

With such episodes to account for, Karkowski’s enthusiasm gradually led him away from the soi-disant centers of expert knowledge in Europe to tiny underground enclaves in Japan, China and the Americas, where he was an active collaborator with, and advisor to, dozens of like-minded “soundheads”. Though he was never a mentor in a formal or professional sense (and I recall at least one review in which his academic peers chastised him for giving a supposedly “anti-rational” lecture), he wasted no opportunities to commune with like minds navigating similar terrain, regardless of their own level of connectedness to the antecedents of any particular “scene”. True to his vow to be a “catalyst for existing forces,” he helped to facilitate that connectedness in a way that did more than just provide “name recognition” for relative unknowns: in at least one case I can think of, he became like an actual parent to a veteran Japanese noisemaker who had never known his biological father.

I anticipate that Zbigniew’s detractors will see this character sketch as a glaring lie by omission, if they’ve made it this far: my encomium doesn’t account for the combative “Mr. Hyde” unleashed during his truly heavy bouts of drinking, or his tendency to malign certain peers as poseurs telling people what they wanted to hear, rather than honestly attempting to push the limits of their own creativity. Yes, there are countless apocryphal tales of poor promoters having to drag Zbigniew’s drunken frame from the bar to the neighboring performance venue, or of avoidable fisticuffs and unsolicited, seemingly out-of-nowhere assessments of “what your problem is,” followed by surgically precise verbal incisions into the heart. I have been on the receiving end of such, including the deathless classic “I’m sure you will be successful with your writing…people love bullshit.” I really have no answer for how an extremely generous and effervescent spirit could also have such a prominent shadow side, and it’s probably for the best that I leave this analysis to others.

Now, I can hardly speak for everyone, but I found these brow-beatings could eventually develop into something more insightful if you remained calm and weathered the storm without lashing out in turn. I forget what I said or did to trigger Zbigniew’s endless capacity for argument on this one occasion, but it resulted in him telling me that he created work that communicated all it needed to say whether you soaked up 50 minutes of it or 50 seconds. In his aforementioned mini-manifesto he offered up a more lucid phrasing of the same general idea: “the real art communicates before it is understood”. Ideally, this would be a sonic art that could capably position itself against that art which merely acts as an initiatory rite to revelations of the artist’s “identity”, and it would be an art that had no need of the “additional context” required by a hopelessly visuo-centric culture (again in his manifesto, Karkowski inveighed against “dogmatic constructions for the eye and intellect…small intellectual games that have nothing to do with the reality of sound”).

It’s also intriguing that Karkowski spoke enthusiastically of attaining “strength” and “power” through sonic means, but this needs to be qualified in light of these terms’ usage elsewhere in marginal electronic music cultures. Karkowski’s vitalistic desire for re-integration into something infinitely more numinous and timeless was unlike the transgressive inclinations of, say, copycat “power electronics” acts, who saw power as a function of successfully excluding themselves.This lustmord-worshipping coterie, much in the same way as the Surrealists embraced the Marquis de Sade, styled themselves as “metaphorical criminals” that “rejected aristocratic reserve and bourgeois hypocrisy in favor of a return to what [they] called authenticity…a real or true self left stagnant under bourgeois norms.”6 As Surrealist dandy André Breton remarked in his panegyric for Sade, “man no longer consents to unite with nature except in crime,” though I believe Karkowski’s work aimed at that same unison without using it as a justification for cruelty or “self-actualizing” via superficial deviations from normative behavior.

Karkowski delighted in pointing out how transgressive postures rarely precluded the creation of “bullshit” music: in fact, in a previous discussion we had about the “No Fun” noise-fest in New York, he recalls “standing in front of the speakers and just laughing” at the mediocrity of a power electronics combo who, by all appearances, seemed to think their BDSM-inspired stage getups and choreographed disdain for the audience would compensate for a sonic impact which barely approached the damage he was capable of doing (smoking P.A. systems were not a totally uncommon feature at Karkowski performance, and in one case one of the toilets at the San Francisco-based Compound venue was allegedly cracked from the unrelenting assault of sub-bass frequencies).

Moments like these can be “badass”, but also much more than that: in making the physicality of sound so abundantly clear, Karkowski tied together all of the loose threads in his Weltanschauung by realizing that we ourselves are vibratory phenomena given a distinct physical form (Karkowski notes how “individual atoms and molecules have vibration as their fundamental characteristics, and are known to be resonant systems”). Our engagement with sound as an expressive medium is then a shift in “narrative gravity” from the story of the self to the story of the known universe. As Harold Bloom says of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, he has an ability to project a “vision that is everything and nothing”; a vision that itself points to “an art so infinite it contains us, and will go on enclosing those likely to come after us”.7

Author’s note: all quotes from Karkowski originally taken from the essay “The Method of Science, The Aim of Religion,” originally retrieved from http://www.desk.nl/~northam/oro/zk2.htm, October 29 2008.

Eric Duggan, “Oprah Fans Trust in Transformation,” St. Petersburg Times, June 21, 2003, p. 15A.

Kuspit, D. (2004). The End of Art. Cambridge / New York: Cambridge University Press.

Borio, Gianmario (2013). “Sound as Process: Scelsi and the Composers of Nuova Consonanza.” In Music as Dream: Essays on Giacinto Scelsi. Eds. Franco Scianname & Alessandra Carlotta Pellegrini. London / New York / Plymouth: The Scarecrow Press.

Ibid.

Guignon, C. (2004). On Being Authentic. London / New York: Routledge.

Dean, C.J. (1992). Pleasures of the Self: Bataille, Lacan and the History of the DeCentered Subject. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bloom, H. (1998). Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books.